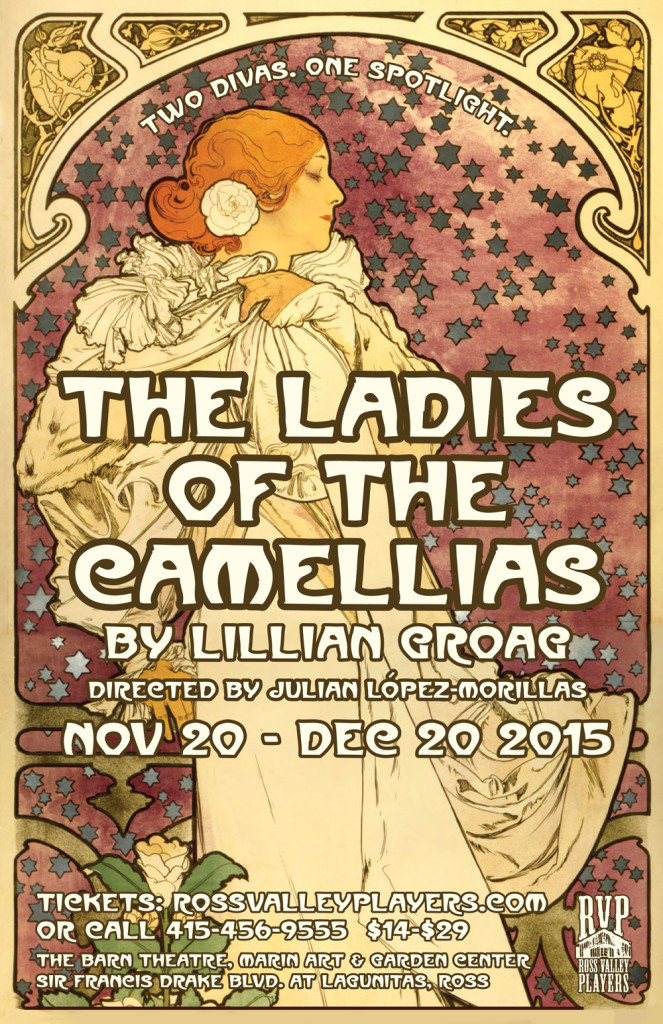

A Message from the Director

After the horror of the events in Paris last week, I told my producer that I couldn’t think of a more difficult time to be putting on The Ladies of the Camellias. A play set in a theatre in Paris, in which the major action is initiated by a radical breaking into the building, armed with a gun and a bomb, and threatening to execute hostages until his demands are met; and yet which bills itself as a comedy—how could we possibly dare, in the climate of terror that has gripped our culture, to ask people to laugh at that?

There is an old saying in the theatre: “comedy is tragedy plus time.” Events that we experience as catastrophic in the immediate present will eventually, with the longer perspective of life experience and the ripening of events over time, recede in memory into a form that can be dealt with– looked back upon, with benefit of wisdom, as something in which we might even find humor.

A century ago, the Western world was terrorized—in a way we might find familiar—by the political movement of Anarchism. Though many leading proponents of the philosophy espoused nonviolence, a small fringe element grabbed the headlines with a campaign of assassination and bombing that precipitated the First World War (through the murder of the Archduke Ferdinand in Sarajevo) and led to the Great Red Scare in this country soon afterwards. The figure of the “bomb-and-whisker anarchist,” popularized by editorial cartoonists, became a caricature as potent and terrifying for our great-grandparents as the symbol of the fanatical jihadist has for our own time.

Not to disregard the national panic that events like these inspired in the long view, violence for political ends has come to be seen as pointless and destructive, and democratic values of tolerance, understanding and diversity can yet hope to prevail. “There is unspeakable sadness in the world,” Sarah Bernhardt remarks in this play; but also, “Life is everything.” And La Duse adds, “No idea backed up by death is a good idea.”

One comic focus of Ladies is the idea that show people are so self-absorbed, so fixated on the practice of their “art,” that they are oblivious to events in the real world outside the theatre walls. These are not the show people that we want to be. We mourn with the people of France for the brutal violence that has been visited upon them. But we look forward, with hope, to a time at which such terrible events may seem as distant as the turn of the twentieth century, and its own conflicts, seem to us.

Julian López-Morillas